Shearing

Through friends of friends, a method that is tried and true among stockmen (and women) I heard of Sonny Gustamantes many years ago. I had gone through a parade of Australian, New Zealand and Spanish shearers, all of whom either slashed the sheep unmercifully when they sheared them, threw them on the ground roughly and kicked them to get up after being sheared, or cut the fleece in such a way that most of it was unusable. In addition, a goodly number were varying degrees of surly to deal with. I had also listened to the frequent talk that good shearers were almost impossible to find, and if you could find one, he/she most likely would live near/around large bands of sheep, and would not travel out of his area for small flocks (less than 100). So I did not have high hopes for Sonny.

Imagine my surprise when he showed up on time, had a well-oiled and professional shearing rig, answered all of my questions with “yes, ma’am, “ or “no, ma’am”, treated my sheep with respect, and did a great job with the wool.

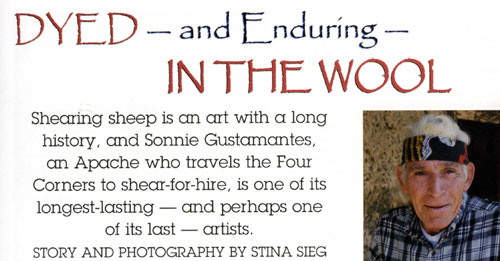

Sonny Gustamantes

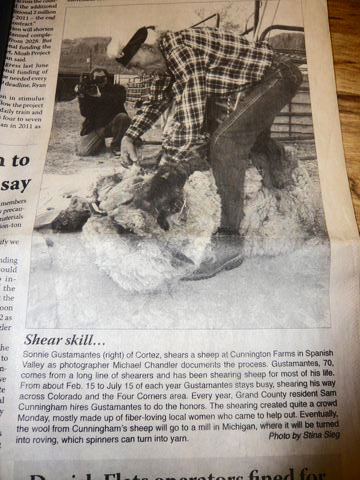

Sonny shearing sheep at Cunnington Farms

featured in the Moab Times Independent

Shearing is a necessary evil, and the challenge of the shepherd is to turn it into a festival and an enjoyable time. Doing a good job preparing for shearing makes the job much, much easier. A month or so in advance, I call all the other people that have sheep in our valley, and work out a time for the shearer to come that will be good for everyone. I make sure that day is good for Sonny. Several days before shearing day, I call everyone and remind them the day is coming up. I make a menu for the lunches the entire crew will have on as many days as it takes to get through shearing, and get all my ingredients together. I get bags for the fleece, tags for identification of the individual fleeces (one to a bag), and bags for the discarded bits, like tags. I stock up with bottled water and cold pop, and lots of “bug spray”. I make sure all the paid help and the volunteers know when and where to be at the appointed time. All these burdensome preparations make shearing day much more enjoyable, believe me.

It is absolutely impossible, however, to have joy when my alpacas and guanacos are being sheared, and everyone within a 20 foot radius has green alpaca spit all over their faces and bodies — but other than that, at Cunnington Farms we work towards having fun and getting the work done. In addition to several paid, burly, young and adventuresome young men, I have a shearing boss who directs the hands in their jobs; to help get another sheep on the shearing floor, to move the shorn fleece off the shearing floor, and take it to the skirting area, to sweep up the wool bits on the shearing floor so they won’t get mixed up with the next fleece, and do any doctoring that is needed (the heavy fleece sometimes conceals a problem or two that can be treated right on the shearing floor). Sometimes someone has to help Sonny hold down a particularly unruly sheep. Sometimes they have to run for water or coffee, more fleece bags, labels or tie twine. And sometimes we all just have to stop and take a break.

After the fleece is shorn, someone takes it to the skirting area. I usually have several women helpers that willingly trade their skirting skills for getting the pick of the fleeces that are shorn. Others come for only a few hours, sometimes to help, and sometimes to watch. I am fortunate that there is a nationally known fleece judge that lives in our valley, and she always is on hand to help people learn how to skirt, and to make comments on all of the fleeces so budding fiber artists can learn about fleece. Occasionally there are video artists, capturing on film what used to be a common event in the West, but now has become an interesting “old-time” experience.

Days beforehand, I make monstrous batches of food, and when we break for lunch, at the discretion of the shearer, everyone is ravenous, no matter how hot the weather is. (We shear in March or April, so if we are lucky, the sweltering heat of Moab has not begun).

We all gather on the porch, and hearty eating does not stop anyone from lots of “yarning,” visiting and networking.

It is hard to go back to work as the afternoon gets hotter, and that big lunch is sitting in tummies, but we manage to continue on and get through the day. Some shearers start with the biggest rams, to get them over early, and some start with the smaller sheep, to get “into gear.” But by the end of the day, ALL the sheep look pretty big!

The second day of shearing is exactly like the first, and if I have a particularly large number of sheep in a year, we have even gone into a third day. Sonny rarely does more than 20-25 sheep a day, and that is fine with me, since he does a careful and thoughtful job on each and every one. It is a little more expensive than if he rushed through it in a day, since I pay helpers by the hour, but to me, it is well worth it.

The best and ultimately easiest way to find a good shearer is by word of mouth from your ranching friends, your breed association, the local Extension Agent, and/or the local vet.

In the last few years, crews of Peruvian shearers often come through any part of the country that might be considered sheep country, and shear for hire. I have had good luck with these on a year or occasion that Sonny and I can’t connect for shearing. Shearers appreciate if one person in an area will make an attempt to gather all the sheep in the area needing shearing, and make an “appointment-type” list of either having the sheep come to one central place (the shearers prefer this), or making a logical sequence for the shearer to move from one ranch to another. Most shearers want to be paid for their work; prices for shearing ewes range from $5 to $8.50 per sheep, and rams are usually $10-15. If someone has let the sheep go several years without shearing, the price usually goes up to $20, as the shearer has a tough time getting through the matted fleece. Occasionally, shearers will shear for the fleeces alone, especially if the flock has excellent wool; but usually those shepherds have plans for the wool themselves, and don’t find a trade appealing.

Shearing IS becoming a lost art, and commercial shearers that shear for a living are in great demand. Happily, in these days of many more small flock owners, a fair number of shepherds are willing to learn how to shear their animals themselves, and set a schedule of doing a few a day. This works exceptionally well if you can physically do it. The moves are not too hard to learn; it is just your body that protests! Most sheep are not mentally scarred for life by shearing, even if the shearer is rough, but either doing it slowly and lovingly yourself, or having a master shearer like Sonny, is the ultimate sheeply dream.

Read an Inside/Outside Southwest Article written about Sonny Gustamantes at Cunnington Farms.